D'var Torah

01/28/2020 08:21:04 PM

"Reading the Signs"

Va'era

Friday, January 24, 2020

I used to think that Pharaoh might have relented sooner than he did during the Exodus story if God had not hardened his heart. According to our next two parashot, Va’era, which contains the first seven plagues, and Bo, which has the last three, Pharaoh hardens his own heart the first five times, and then God hardens it after the last five plagues. Perhaps Pharaoh would have let our people go after five, or six, instead of subjecting his own people to so much more suffering, including the worst of them, makat b’chorot, the slaying of the firstborn of Egypt.

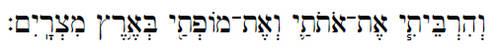

Tradition has a lot to say about Pharaoh’s heart, and how stubborn he is in refusing to relent to God’s demands. God tells Moses (Ex. 7:3):

“I will harden Pharaoh’s heart

“and I will multiply My signs and My wonders in the land of Egypt.”

Rashi comments: “As Pharaoh has acted so wickedly and resisted Me, and I see that the other nations have no interest in repenting, it is better that he should harden his heart, so as to multiply My wonders against him.” In other words, I will harden Pharaoh’s heart precisely so that I can send more plagues, and thus show the world how powerful I am.

The medieval Italian commentator Sforno suggests, as Rashi does, that Pharaoh might have let us go sooner if not for God’s intervention in his brain: “The Almighty sent the plagues to stir the Egyptians to repentance…and there is no doubt that, had not Pharaoh’s heart been hardened, the latter would have let the Israelites go, but his action would not then have been motivated by sincere repentance and submission to the Divine will, but merely because he could no longer bear the suffering of the plagues, as his servants intimated, ‘Do you not yet know that Egypt is destroyed?’ But this would not have constituted true repentance. Had Pharaoh wished to submit to God and truly return to God, nothing would have stood in his way. But God hardened his heart, fortified his resistance to enable him to endure the plagues and refrain from letting the Israelites go: ‘in order to show these my signs in the midst of them,’ that they might thereby acknowledge My greatness and goodness and turn to Me in true repentance.” So for Sforno, since Pharaoh won’t truly repent anyway, God will use to plagues to demonstrate God’s power to Israel.

Lest you think the Rabbis are sympathetic to Pharaoh, since it seems like he had little free will left by the end of the Exodus story, here comes Rambam. He teaches in Mishneh Torah that if someone’s sin is great enough, his opportunity to repent will be made more difficult so that God can punish him. He writes: “Since Pharaoh began to sin on his own initiative and caused hardships to the Israelites who dwelled in his land, judgment necessitated that he be prevented from repenting so that he would suffer retribution. Therefore, the Holy One of Blessing hardened his heart.”

From a more modern perspective, we have seen how hardening our own hearts can hinder our ability to exert free will. We don’t need God to intervene to become as stubborn as Pharaoh. We’re very good at achieving that stubbornness on our own. Just look at how polarized political views have become in so much of the world (yes, I’m talking about you, Israel and the United States). It’s become a sin to admit that the other side might have something of value to say. But when our hearts become hard, we don’t want to hear it (and yes, I’m talking to you, members of the U.S. Senate who made your minds up about impeachment before the trial started).

Most of us find ourselves guilty, especially when we only watch the news channel or read the newspaper that reflects our politics or ideas about society or science or whatever we’re fighting about this week. Pharaoh knows his people are doomed—his courtiers even warn him after the plague of locusts:

“How long will you let this one be a snare to us?”

“Let this people go and worship the Eternal their God.”

“Can you not see that Egypt is lost?”

It’s easy to train ourselves to ignore the signs and warnings when we’re sure we’re right. We’ve known about the dangers of climate change for over forty years and still we resist trying to right the ship before it’s too late. We knew about the dangers of smoking tobacco for decades before we took action. A small minority of Jews took the Nazis seriously until it was too late. Perhaps we’re just naturally optimistic that everything will turn out okay if we just wait, or perhaps it’s easier to harden our hearts and pretend nothing’s wrong. Pharaoh isn’t an anomaly of history—he’s an archetype.

The Etz Hayim Commentary, in pointing out that Pharaoh does plenty of heart-hardening before God steps in, suggests that “in the beginning of the process, Pharaoh was equally free to be generous or to be stubborn. Every time he chose the option of stubbornness, however, he gave away some of his free will. Each choice made it more likely that he would choose similarly the next time, both to spare himself the embarrassment of admitting that he was wrong and because he now had the self-image of a person would not yield to Moses’ pleading.”

After all these millennia, when will we stop falling into Pharaoh’s trap? It’s okay to admit when we’re wrong. It’s okay for our old views and positions to evolve into new ones. And if we learn anything from Pharaoh’s intransigence, it should be that it’s never too late to turn back and change our ways—until it is. Only then will we have become so hard-hearted as to seal our own fate—without any extra “help” from God.